Artist in Residency in Cornwall (part I)

I'd like to take you with me on a journey in a beautiful and authentic part of the UK which I will always hold close to my heart. I've had a wonderful and very inspiring time last May in Cornwall during my artist in residency. This opportunity was part of the prize for New Ceramics I've won in Oldenburg in 2023, kindly offered to me by the Werkschule Oldenburg.

As an artist, it was a most precious gift to have the space to slow down and to be creatively refreshed and inspired. Time to wander in the Cornish nature and to discover the history of mining English porcelain.

‘To get in the creative zone, ideally,

you need time, space, tranquility.

Being creative is a place you need

to travel to in your head.

You can't get there if too much

real life is in the way.

Creativity lives in paradox:

serious art is born from serious play.

Making art begins with hay

while the sun shines. It begins with

getting in the now and enjoying your day.

It begins with giving yourself some

small treats and breaks.

Creative living requires the luxury of

time which we carve for ourselves.’

I stayed in a charming shepherd's hut at Trenince farm in the wilds of Celtic Cornwall. This unique place at the edge of the village of Luxulyan, is created by the lovely artist Wendy Rolt. It was such a pleasure to meet her and share our thoughts on creativity and being an artist, our path of spiritual growth and our love for nature.

I was surrounded by a fairylike forest and huge granite stones that are part of the Cornubian Massif. Carpets of bluebells covered these woodland floors and dappling sunlight enlightened the moss on ancient tressed trees in the most strange shapes.

Luxulyan Valley is Cornwall's secret rainforest. It is an excellent example of deciduous Atlantic wet woodland. This temporate rainforest is rich in fungi with mosses, liverworts, lichen and ferns, growing not just on the trees but also on rock faces. I love all these typical species and I was so delighted to be surrounded by them everyday. They are part of the work I make and a huge source of inspiration.

When I was searching for a suitable place for my artist residency I knew I needed a quiet place situated in nature and there had to be a link with porcelain. As I love the UK and knew about the mining of porcelain in Cornwall, I started looking here and found the perfect place at this retreat. The description of Wendy's place really resonated with me and I immediately knew I would feel at home here. And I really did!

This unique place was surrounded by nature, silence, birdsong, beauty and the most beautiful sunsets. I took me some days before I could really slow down and taking the time to be immersed by the landscape and atmosphere of Cornwall.

Having this residency was such a luxury as it helped me to crave time for myself, to watch this new world with wonder and to connect with nature and its rhythms.There was time to be still to watch the wildflowers in the field and hear the wind rustling in the trees. And slowly new ideas took shape in my head.

I've used my time to discover the origins and history of English porcelain and to study the Cornish flora. In my next blogpost I'll share more about all things related to its amazing and inspiring nature.

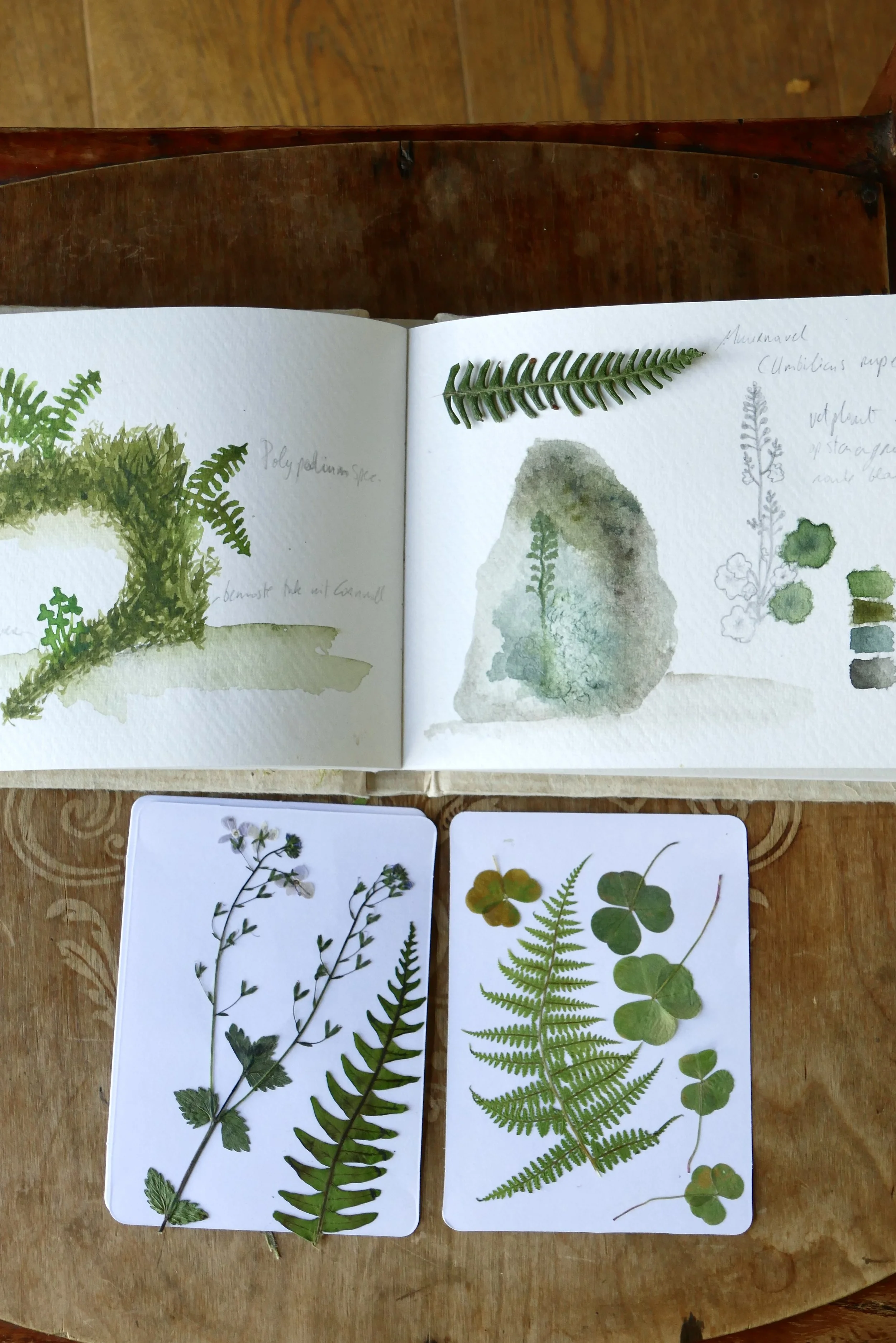

I had the time to read, reflect, write, draw and paint. On my walks and adventures I collected flowers and plants which I've dried in my travel flower press. I filled a new notebook with my experiences, thoughts, ideas, dried flowers and so much more that interested me. This notebook will be my guideline for the coming time to create new work.

The Saints Way (or ‘Forth an Syns’in Cornish) is a pilgrimage route which passes through the wild fields of this retreat. It's a fascinating pilgrim path that winds through the tranquil heart of Cornwall, offering a glimpse into the county’s spiritual and historical past. Beginning in the charming seaside town of Padstow, the route follows ancient tracks and crosses historic bridges once travelled by Celtic saints and early Christian pilgrims.

I've been walking different parts of this pilgrimage path and one of the highlights was Helman Tor. This Neolithic hill fort is one of the highest points in Cornwall. It was definitely worth the climb and the view overlooking the marshy ground of Red Moor was just stunning!

Another day I walked the other direction of the Saints Way to the hidden kingdom of Treffry. A place where nature and industry emerges and which really fascinated me. It's a historic landscape with the famous Treffry Viaduct, which has been reclaimed by nature and is now a have for wildlife. However, traces of the porcelain industry are still visible.

It was such an impressive experience to walk on these ancient paths where hundreds years ago, people were working hard to quarry china clay.

The Treffry Viaduct is the only known viaduct in Britain to combine both a horse-drawn tramway and a water channel (known as a leat).It's built by Joseph Thomas Jeffry (1782-1850). He became the largest employer in Mid-Cornwall in the 19th century and relied upon hundreds of local men and women to build and run his industrial empire.

The Velvet Way or the Long Drive (ca. 1900) is a beautiful and quiet walking path that breathes history under a canopy of trees. I really loved walking here!

Some remembrances of the industrial clayworks past;

a forgotten piece of china clay,

a leat,

and a rusty trace of the tramway.

The Carmears Leat, running through the viaduct and along the top of the Valley, powered a waterwheel which hauled wagons up an inclined plan, enabling the tramway to function in order to transport the china clay.

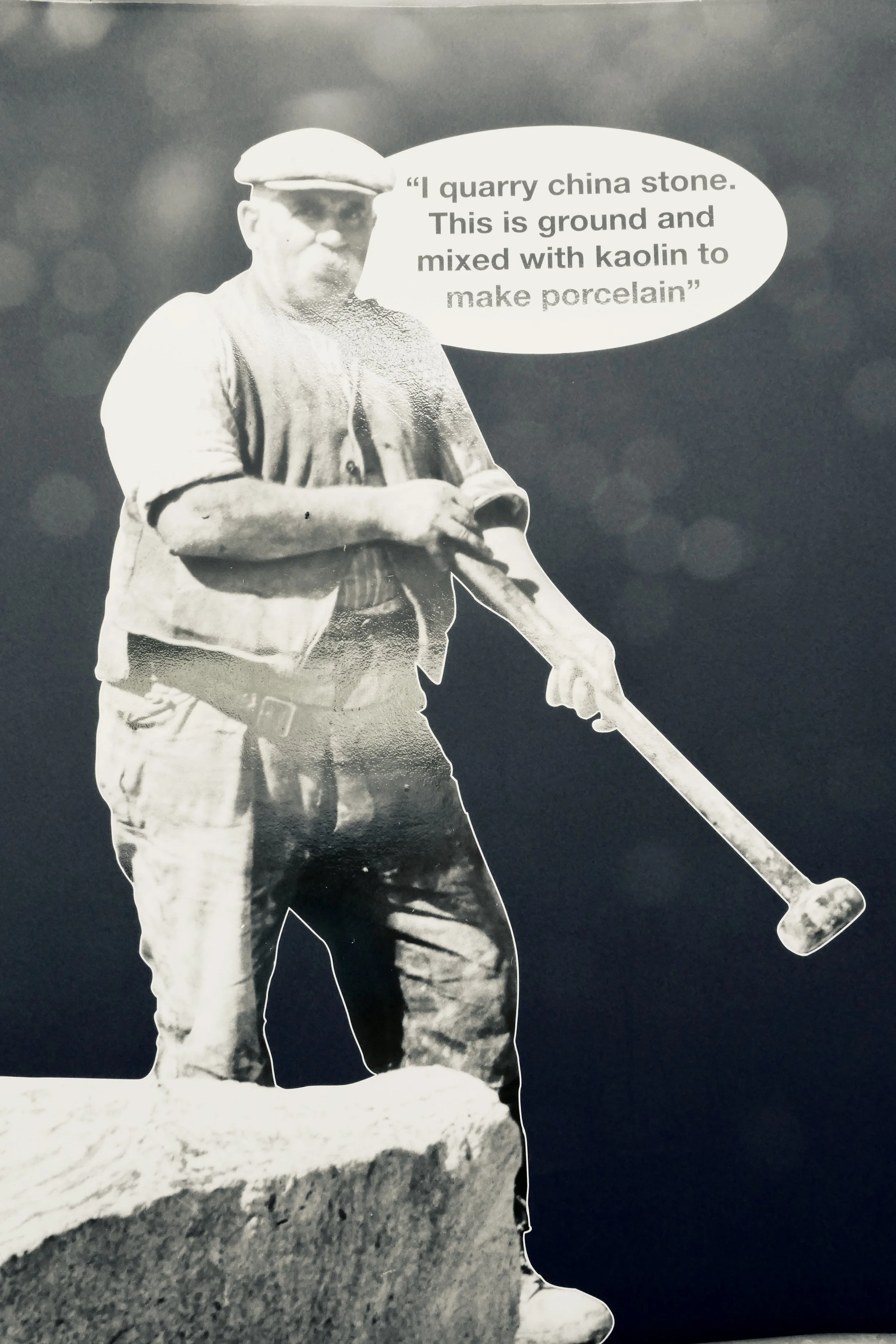

Another highlight of my residence was the visit at Wheal Martyn Museum. This was such an interesting place as it clearly explains and shows the origins of one of the main ingredients of porcelain; kaolin or china clay.

The mineral name Kaolin is derived from ‘Kauling’ (hill or ridgel, a place where china clay was traditionally found in China).

China clay or kaolin, a powdery white mineral, was formed in Cornwall and Devon by the gradual decomposition over ages of some of the granite rock which runs from Dartmoor to Land's End. It was discovered in the mid-eighteenth century by a Plymouth chemist called William Cookworthy, who was looking for one of the secret ingredients which the Chinese had used for a thousand years to make porcelain.

The method of winning china clay did not change much from the eighteenth century to the early twentieth century. Now large scale operation has changed the industry although the principles remain the same.

This picture shows a clay pit where they still quarry china clay nowadays. There are now 20 working pits in the UK, comparing to 120 smaller pits working in the 1870s.

The Cornish landscape is shaped by its porcelain mining as you can see in the picture below. This region is also called ‘the Cornish Alps’ which refers to these white ‘tips' or pyramids. For every 10 tons of material dug from the ground, about one ton is china clay. The rest is sorted with rock and waste sand dumped to form tips.

The picture below shows a typical clay pit scene of the St. Austell area around1920.

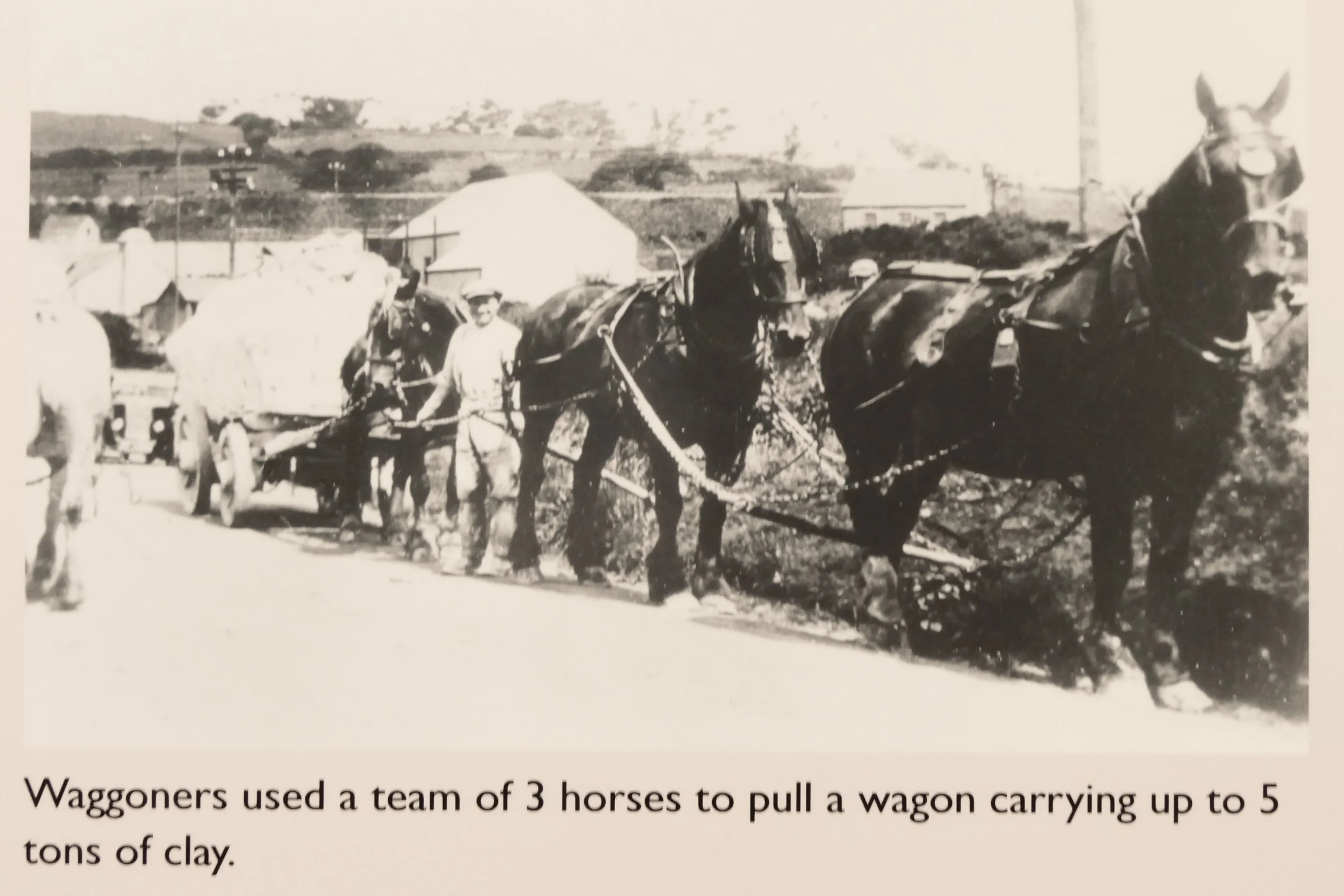

China clay is mined in open pits. These gradually became larger and deeper as demand for china clay grew and more clay was dug out. The water used to loosen the clay, together with the rock waste, all gathered at the bottom of the pit.

The finer sand and the china clay mixes with the water to form a sludgy liquid called slurry. The slurry was pumped to the surface to be treated and refined to get the best china clay.

At the Wheal Martyn Museum there are still some remains of one of those waterwheels.

The Clay Dry or Pan Kiln;

for around 100 years, clay was dried naturally on open-air sun pans and was dependent on good weather. Once it became solid enough to be cut into blocks, it was stacked on drying shelves, known as air dries, for the air to complete the process.

In the mid-nineteenth century the slow process of sun pan thickening and air drying was gradually replaced by deeper thickening tanks and drying on long floors heated by coal fires, as seen below.

The dries were roofed and built alongside settling tanks.

Not only men worked at the clay industry. Here you can see ‘ball maidens’ at work. Although they were not in great numbers and would be taken on to do specific tasks when needed.

Beside the pan was a storage area or 'linhay’ for dried china clay before being transported.

I hope this blogpost was helpful to get more insight in the process of china clay mining and how this industry has shaped Cornwall in many ways.